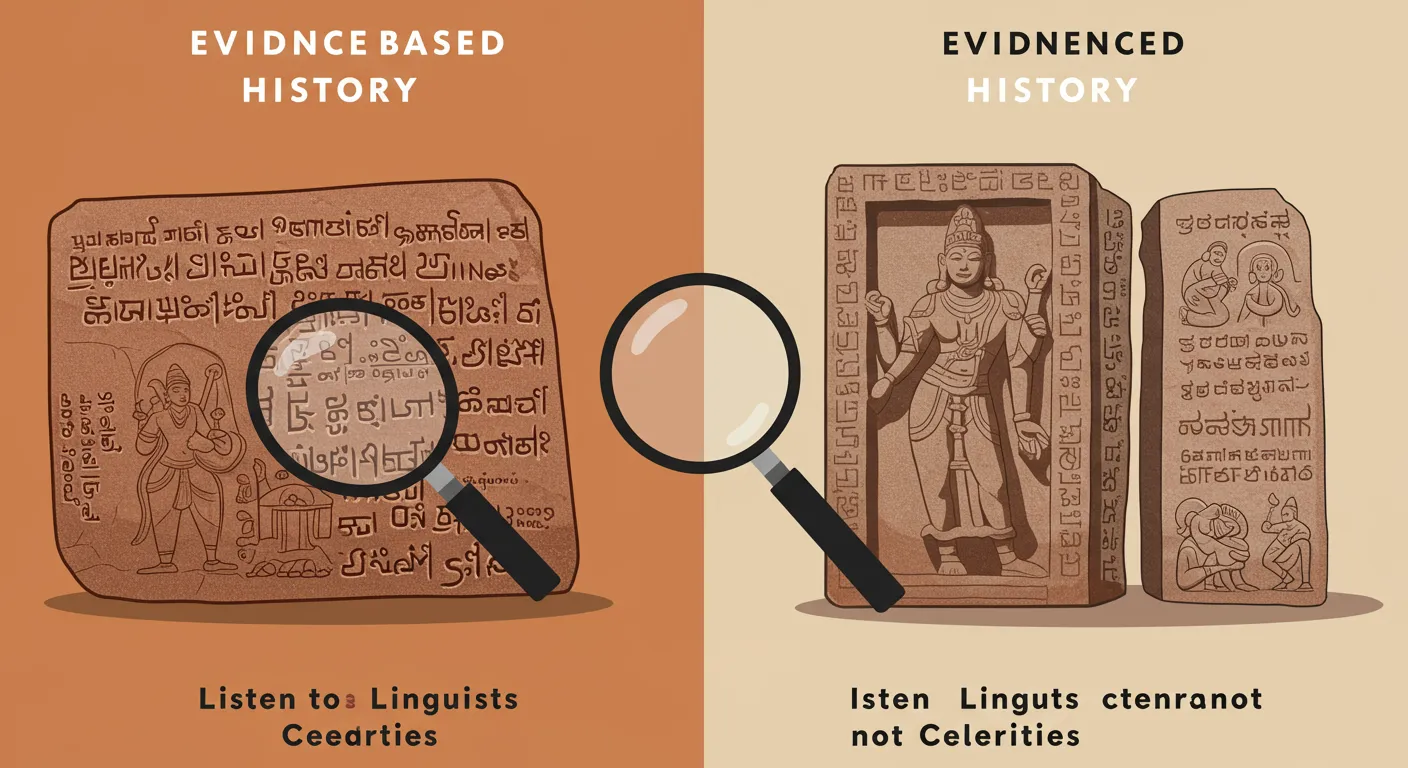

The claim that Kannada is the oldest Dravidian language than Tamil (or vice versa) is a popular talking point but not supported by scholarly evidence. Linguists and historians agree that Tamil has much older attested records than Kannada, though neither language “evolved from” the other in any direct way. Both Tamil and Kannada descend from a common South-Dravidian ancestor (often called Proto-Tamil-Kannada) and branched off long before written history. In terms of documented history, however, Tamil comes first. Early Tamil inscriptions and literature date to the first millennium BCE, whereas the earliest Kannada records appear only in the 5th century CE. This blog examines peer-reviewed research, epigraphical finds, and linguistic studies to explain the consensus view. We will summarize the key evidence—inscriptions, literary works, and language structure—for each language, and debunk celebrity claims with solid scholarship.

Dravidian Origins and Language Family

The Dravidian languages form a family native to South Asia. Proto-Dravidian, their prehistoric ancestor, was spoken long before writing; it split into several branches in ancient times. In particular, the South Dravidian I subgroup includes Tamil, Kannada, Malayalam, and a few smaller languages. Within this group, Proto-Tamil-Kannada is reconstructed as the common ancestor of Tamil and Kannada (along with Malayalam). Importantly, this branching occurred well before any surviving inscriptions: experts estimate that Tamil and Kannada began diverging from each other more than 2,000 years ago. For example, writer Badri Seshadri notes that linguists date the divergence of Tamil and Kannada to roughly 2,500–3,000 years ago.

Consensus among linguists is that neither language “came from” the other. The Indian Express summarizes:

“The split between Kannada and Tamil is older than any of the surviving literary or epigraphic evidence. Their common ancestor, […] is conventionally termed Proto-Tamil-Kannada. Both [languages] branched off from this unattested language; it is meaningless to say that Kannada came from Tamil or Tamil from Kannada.”

In other words, Tamil and Kannada are sister languages. Any statement implying one is the “mother” of the other is linguistically baseless. Likewise, Kannada is not derived from Sanskrit—both Kannada and Tamil have borrowed from Sanskrit, but each is fundamentally Dravidian in structure. Historical linguistics focuses on systematic sound changes and grammar, not modern vocabulary or prestige.

Below, we compare the oldest evidence for each language on its terms.

Tamil: Ancient Inscriptions and Literature

Tamil has one of the oldest literary traditions in India. Archaeology and epigraphy show that written Tamil dates back over two millennia. In particular, inscriptions in Tamil-Brahmi script (a southern variant of Brahmi) have been found across Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and parts of Sri Lanka, often on cave walls, pottery, and rock surfaces. These texts are typically short dedications or donor records, but they are crucial because they date Tamil beyond the start of the Common Era.

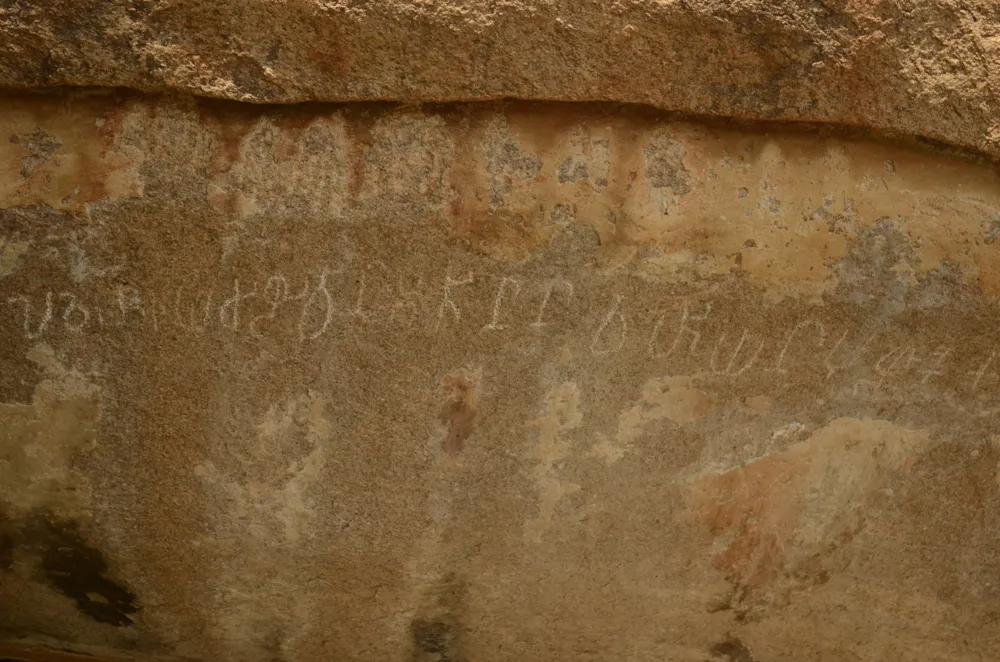

An example of a Tamil-Brahmi inscription (c. 3rd–1st centuries BCE). Research confirms that “the Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions are the earliest available written records in Tamil and the Dravidian family of languages.”

Archaeologists date these Tamil-Brahmi texts to roughly 3rd–1st centuries BCE. Carbon-14 tests on associated charcoal and paddy grains suggest dates as early as the 5th–4th centuries BCE, though some scholars debate these early datings. Notwithstanding the debate, even conservative estimates place the oldest Tamil inscriptions well centuries before the earliest Kannada evidence. A recent summary notes: “The Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions are the earliest available written records in Tamil and the Dravidian family of languages.” Moreover, Tamil Nadu has yielded many such Brahmi inscriptions from between the 3rd and 1st centuries BCE. For example, a 2nd-century BCE engraving from Arittapatti (near Madurai) records a local chief’s gift, proving Tamil literacy in the pre-Christian era.

In addition to inscriptions, classical Sangam literature attests Tamil’s antiquity. While the legends of Sangam academies are mythical, scholars estimate that much of the extant Sangam poetry was composed between about 300 BCE and 300 CE. These Tamil poems (on love, ethics, history, etc.) and the earliest Tamil grammar (Tolkāppiyam) solidify Tamil’s continuous literary record from antiquity. The overall picture is clear: Tamil was written and read in South India long before any written Kannada.

Key Features of Early Tamil

- Script: Early Tamil was written in the local Brahmi variant (Tamil-Brahmi) and later evolved into the Tamil script. Vowels and consonants show only native Dravidian sounds, without aspirates.

- Phonology: Tamil preserves some ancient Dravidian features (e.g. lack of voiced/voiceless stop contrast), though it innovated others (for instance, Tamil cevi vs. Kannada kivi, reflecting a sound change in Tamil). This demonstrates that Tamil is as “conservative” as any Dravidian language, but not uniquely so.

- Literature: Works like Tolkāppiyam (ancient grammar) and Sangam anthologies (poems) attest Tamil’s long literary history, satisfying India’s “classical language” criteria due to its independent tradition and ancient texts.

Together, the archaeological and textual record gives Tamil a documented history stretching back at least to the first millennium BCE. No comparable Tamil script or literature older than 500 BCE is known, but even from the 3rd–2nd centuries BCE onward Tamil stands as a documented language.

Kannada: First Inscriptions and Texts

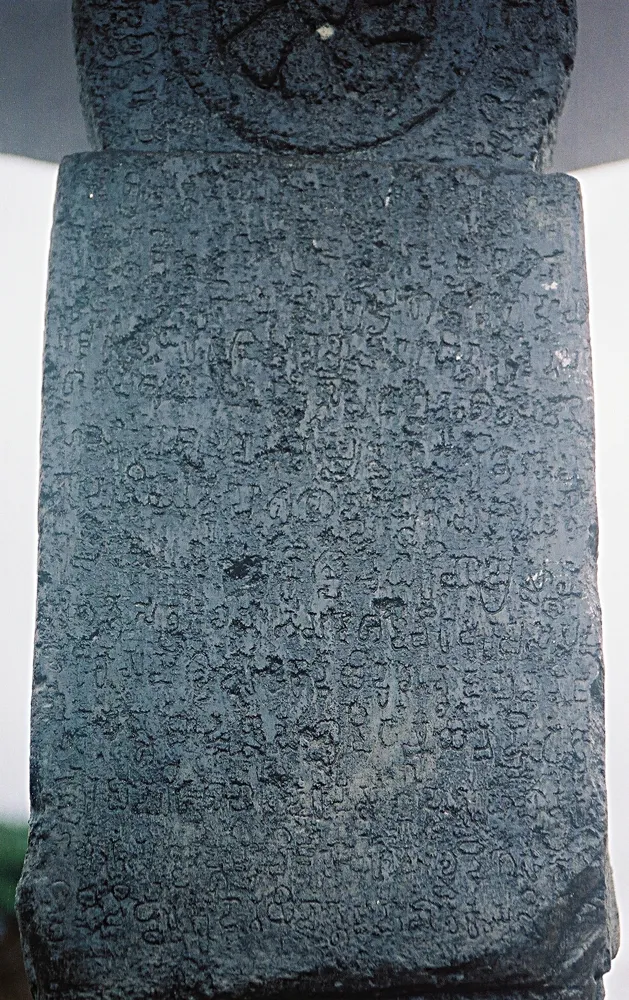

Kannada’s documented history begins much later. The oldest known Kannada inscription is the Halmidi inscription, dated c. 450 CE. Discovered in Karnataka’s Hassan district in the 1930s, this stone pillar inscription (in Old Kannada script) records a village donation. Scholars note: “Kannada has the second oldest literary tradition of the four major Dravidian languages. The oldest Kannada inscription was discovered at […] Halmidi and dates to about 450 CE.” In other words, the earliest Kannada writing post-dates Tamil’s earliest records by roughly 800–1,000 years.

The 5th-century CE Halmidi inscription (old Kannada script). Inscriptions like these mark the beginning of written Kannada history. Scholarly sources confirm Halmidi (c.450 CE) as the oldest Kannada inscription.

After Halmidi, other Kannada inscriptions appear from the 5th–6th centuries CE onward, often associated with the Kadamba and Ganga dynasties. The surviving early Kannada literature also starts late. The first significant Kannada text we have is Kavirajamarga, a royal poetry anthology from the 9th century CE. (Any earlier Kannada works have been lost or were oral.) By contrast, Tamil already had several centuries of written poetry by that time.

In sum, Kannada’s epigraphical record begins around the mid-1st millennium CE. Three historical stages of Kannada are recognized: Old Kannada (c. 450–1200 CE), Middle Kannada (1200–1700), Modern Kannada (1700–present). This timeline underscores that Kannada’s written tradition is younger than Tamil’s by many centuries.

Key Features of Early Kannada

- Script: Old Kannada script developed from a southern Brahmi derivative and is closely related to Telugu script.

- Grammar: Early Kannada inscriptions and literature already show typical Dravidian structure (SOV word order, agglutinative suffixes). By the medieval period, Kannada had absorbed many Sanskrit loans (as have most South Indian languages), but its core grammar remained Dravidian.

- Literature: Aside from inscriptions, early Kannada poetry (e.g. Kavirajamarga, Jain didactic poems of the 7th–8th centuries, and later Bhakti literature) flourishes only from the medieval period onward, well after Tamil’s Sangam era.

Thus, while Kannada is certainly an ancient language with a rich heritage, its earliest attested records begin far later than Tamil’s.

Comparing the Evidence

To summarize the timeline of evidence:

- Proto-Dravidian (prehistory): Tamil and Kannada share a proto-language spoken perhaps 2500+ years ago. Linguists reconstruct Proto-Tamil-Kannada as an intermediate stage, but no written record of it survives.

- Tamil inscriptions: Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions appear by at least the 3rd century BCE (with some estimates even earlier). These are the first written Dravidian texts anywhere.

- Tamil literature: Classical Sangam poetry (approx. 300 BCE–300 CE) provides extensive written Tamil content.

- Kannada inscriptions: The first full Kannada inscription (Halmidi, c.450 CE) comes nearly a millennium later.

- Kannada literature: Earliest surviving Kannada poetry/book (Kavirajamarga, 9th c. CE) follows much later.

This staggered timeline makes it clear which language has the older documented tradition. Importantly, as linguistic scholars emphasize, these dates reflect documentation, not the absolute age of the speech. Both languages undoubtedly existed long before their first inscriptions. Still, the data show Tamil’s written form predates Kannada’s by centuries.

On the linguistic side, shared features prove their common origin. Tamil and Kannada have the same typology (SOV, agglutinative with case suffixes) and many cognate roots. For example, Tamil amma “mother” and Kannada amma are cognates reflecting their common inheritance. But each language also innovated independently. As ThePrint notes, “Old Tamil… was composed in thriving new trading towns with rice-farms,” becoming the first South Dravidian language with writing. Kannada’s ancestor branched off earlier and only later acquired writing and literature.

Thus experts often say it is misleading to label one older. The Indian Express rightly points out that “it is meaningless to say that Kannada came from Tamil or Tamil from Kannada”, since both come from an earlier Proto-Dravidian source.

Busting Myths: Celebrity Claims vs. Scholars

Recently, public figures have weighed in on this question, often with bold but unsupported statements. For instance, actor Kamal Haasan declared that “Kannada was born out of Tamil”. This claim ignited controversy but has no foundation in linguistic science. Reputable scholars quickly rebutted it. As one linguist writes:

“The split between Kannada and Tamil is older than any of the surviving evidence. Their common ancestor… is conventionally termed Proto-Tamil-Kannada… Both branched off from this unattested language; it is meaningless to say that Kannada came from Tamil or Tamil from Kannada.”

Likewise, writer Badri Seshadri explains that “Tamil and Kannada are sisters” diverging about 2,500–3,000 years ago. In the same interview, he notes that some people in Karnataka erroneously claim Kannada is merely Sanskrit-derived. He clarifies: “All South Indian languages have loanwords from Sanskrit, but Tamil has resisted them more than others”. In other words, Kannada did not “derive” from Sanskrit any more than Tamil did; the Dravidian languages simply share some borrowed vocabulary.

Key Takeaway: Celebrities or politicians are not experts in historical linguistics. Claims like “Tamil is the mother of all languages” or “Kannada was born from Tamil” are nationalistic myths, not facts. In a democracy, freedom of speech allows anyone to speak, but readers should weigh such claims against research. The scientific consensus—from linguistics, archaeology, and epigraphy—unambiguously shows Tamil’s attested history is older. Tamil has written records from ~3rd century BCE onward, whereas Kannada’s first evidence is only ~450 CE.

When evaluating such debates, it helps to remember a simple principle: trust the experts and evidence. As the historian-cum-writer of ThePrint commentary asserts, questions of language history are best answered by “scientists, not celebrities”. Indeed, peer-reviewed studies and archaeological reports (not talk-show soundbites) give us the facts. For example, comparative reconstruction by linguists has produced Proto-Dravidian forms, and epigraphers like Iravatham Mahadevan have painstakingly published corpora of Tamil-Brahmi texts. This evidence-based approach leaves little room for sensational claims.

Conclusion

In sum, Tamil is attested much earlier than Kannada. The oldest Tamil texts (inscriptions in Tamil-Brahmi) date to the last centuries BCE, while the earliest Kannada inscriptions (e.g. Halmidi) are from the 5th century CE. Tamil’s Sangam literature further cements its ancient pedigree. However, it is important to recognize that language “age” in terms of speakers is unknowable; all living languages evolved from ancestral forms. What we can say with confidence is that Tamil’s written tradition is older, and that Tamil and Kannada share a common linguistic heritage rather than a parent–child relationship.

Readers should rely on scholarly research when exploring such cultural questions. Archaeologists and linguists use rigorous methods—carbon dating, deciphering inscriptions, and systematic grammar comparison—to build the historical picture. In contrast, unsubstantiated claims from non-experts (however famous) are often colored by politics or emotion. As Badri Seshadri observes, the Tamil–Kannada debate has long been “political hot topic,” but the facts of history transcend regional pride.

By focusing on the evidence—epigraphy, literature, and comparative linguistics—we see that Tamil holds the older documented legacy, while Kannada, though ancient, registers in records centuries later. Both languages are treasures of the Dravidian family. Ultimately, the scholarly consensus is clear: Tamil’s roots in the written record run deeper than Kannada’s. The reliable path to understanding such questions is through archaeology and linguistics, not entertainment headlines.

Sources: Historical overviews and epigraphic reports by Mahadevan, Krishnamurti, and others; encyclopedia entries (e.g. Britannica) on Tamil and Kannada; and recent analyses by linguists and historians.